This post was written by Martin Holmes, Bodleian Libraries(link is external), University of Oxford:

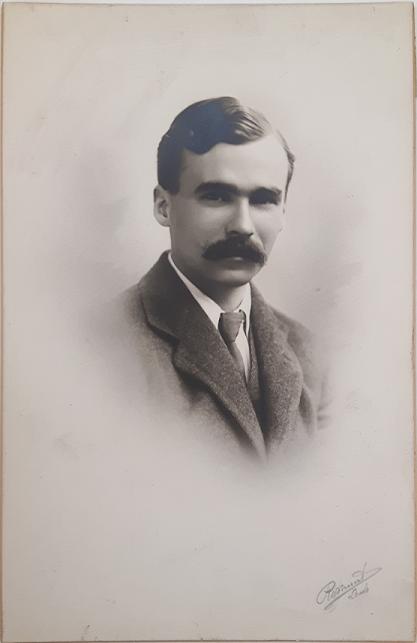

Photo of George Butterworth, ©Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

5th August 2016 marks the centenary of the death of George Butterworth, one of the most promising English composers of his generation, whose life was cut short in the carnage of the First World War. Although many artists, writers and musicians lost their lives in the Great War, on both sides of the conflict, Butterworth is perhaps the one who has obtained most prominence and has, in some respects, come to represent this Lost Generation.

George Sainton Kaye Butterworth was born in London on 12th July 1885. His father was a solicitor for the Great Western Railway and his mother had been a professional singer, so there was music in his blood. The family moved to York in 1891 so George’s formative years were spent in Yorkshire, where he attended Aysgarth Preparatory School. Here he learned to play the piano and organ and showed an early interest in composition. Three hymn-tunes, apparently from this period, survive in a scrapbook which his father compiled which is now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Viewing the many tributes and other memorabilia contained in this volume is a moving experience.

From Aysgarth, Butterworth won a scholarship to Eton. His housemaster’s reports reveal a somewhat rebellious teenager but he excelled in sport and musical activities, conducting an orchestral Barcarolle of his own at a school concert in 1903. He managed to rally his academic work sufficiently to gain a place at Trinity College, Oxford in 1904 to study ‘Greats’ (Classics) but left university with only a third class degree, largely because of the amount of time he spent on musical activities.

While at Oxford, George made several lasting friends, including Hugh Allen and fellow students F.B. Ellis, Francis Jekyll and R.O. Morris. He also met Vaughan Williams and Cecil Sharp and, from 1906, developed an interest in folk music, joining them in field trips to record what they could of a dying oral tradition. Folk music was to have a profound influence on Butterworth’s own musical style, freeing him from what Vaughan Williams saw as the unhealthy influence of Schumann and Brahms and, “what may be described as the ‘Oxford manner’ in music – that fear of self-expression which seems to be fostered by academic traditions”.

On leaving Oxford in 1908, George’s life lacked any clear sense of direction. For a while, he joined the small team of music critics for The Times but, although he proved to be an effective music critic, by the summer of 1909 he had had enough and decided to change direction by applying for the post of assistant music master at Radley College. There he was able to renew his links with nearby Oxford, including making the acquaintance of the young Adrian Boult who was, by that time, an undergraduate at Christ Church.

After only a year at Radley, he went to the Royal College of Music to consolidate his musical skills, but he did not settle to that either and was soon disillusioned with the weekly round of traditional harmony exercises and the like. He left in November 1911 to devote his time to composition and the collecting of folk songs and dances, supported financially by his father who had, by now, given up all hope that George would follow him into a legal career. He was also to develop a passion for folk dancing and became an expert Morris dancer, assisting Cecil Sharp with summer schools and dance demonstrations.

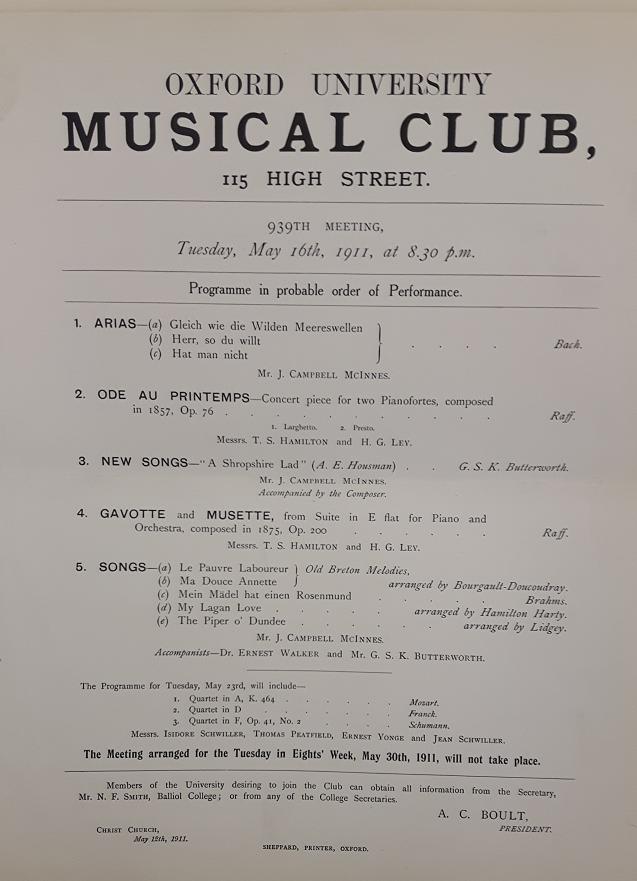

1910-11 saw the composition of two sets of songs to words from A.E. Housman’s A Shropshire Lad and Two English Idylls for small orchestra. Copies of Housman’s nostalgic poetry could be found in the pockets of many British soldiers in the trenches of the First World War and, despite the poet’s known antipathy to musical settings of his words, they inspired many songs, of which Butterworth’s are among the finest. They were to be his first compositions to make it into print.

Program for a concert on May 16, 1911, that featured Butterworth's A Shropshire Lad, © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Butterworth appeared to show no interest in writing symphonic music, preferring instead a rhapsodic style based on folk tunes, in the manner of Vaughan Williams’ Norfolk Rhapsodies (1906-7). The Two English Idylls show an assured, impressionistic handling of orchestral forces and were first performed in Oxford Town Hall on 8 February 1912. His music came to national attention when his next orchestral work A ‘Shropshire Lad’ Rhapsody was premièred at the Leeds Triennial Festival of 1913. It takes much of its musical material from the first of the songs, ‘Loveliest of trees’, and is generally considered to be Butterworth’s finest piece. One further work was completed before the War – a third orchestral idyll entitled The Banks of Green Willow, based on the folk song of the same name. With this work, his friend Adrian Boult made his debut as a professional conductor on 27 February 1914.

Shortly after the outbreak of war, Butterworth enlisted in the army, along with several of his close musical friends, and was sent to France in August 1915. A fastidious and highly self-critical composer, clearly aware that he might not return from the front, he destroyed all the music manuscripts he did not consider to be worthy of preservation. One unfinished work he did preserve, in the form of an orchestral fantasia which has recently been treated to two different completions.

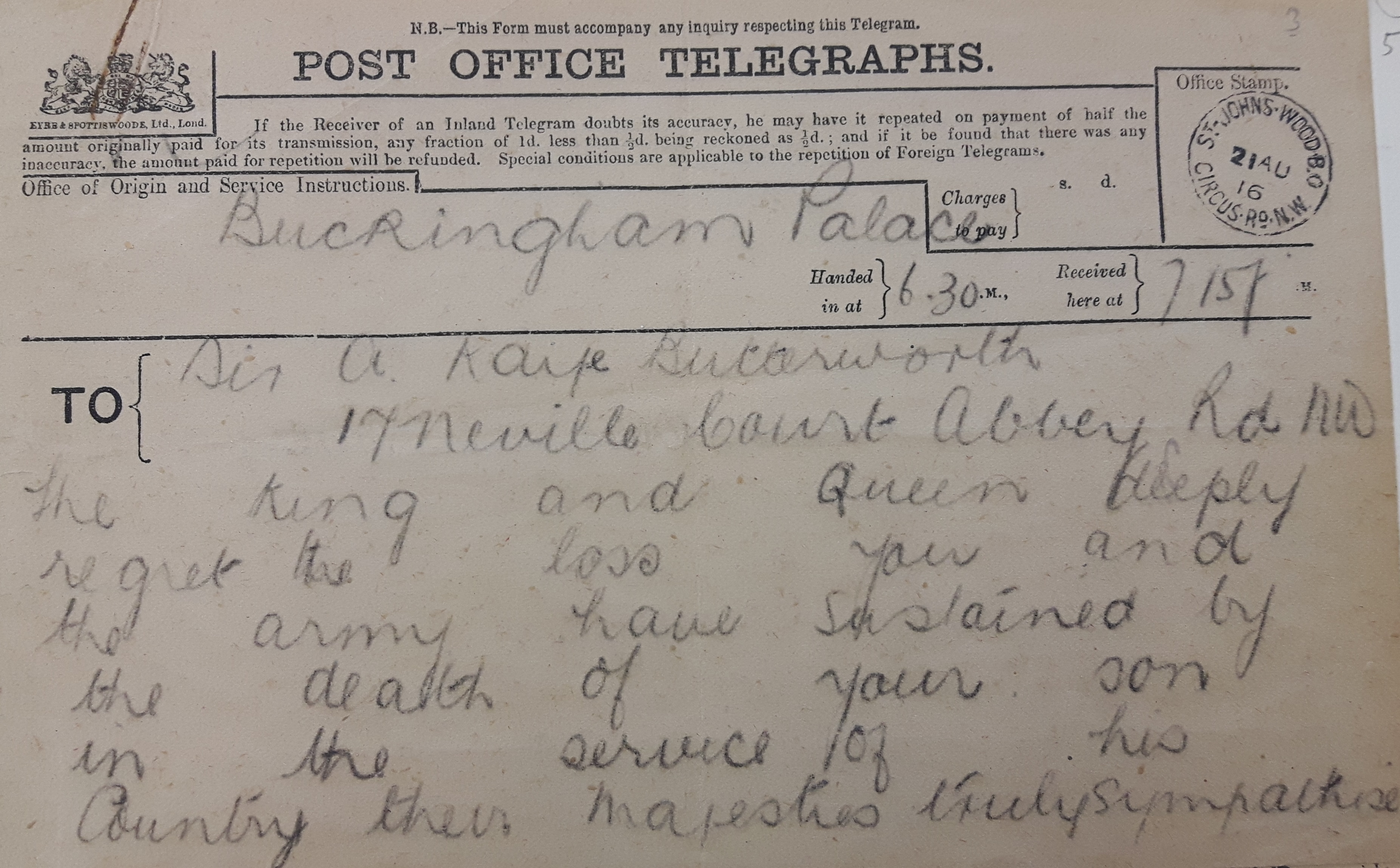

As a soldier, George was clearly well loved and respected by his men. He had the qualities of a natural leader and his gallantry at the front led him to be recommended for a Military Cross in July 1916 which he modestly failed to mention in his letters home. He had been responsible for the hazardous operation of digging what became known as ‘Butterworth Trench’ near Pozières. Not long afterwards, early on the morning of Saturday 5 August 1916, he was killed by a sniper’s bullet. His body was never recovered.

Telegram from Buckingham Palace upon the occasion of Butterworth's death, © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

Butterworth’s reputation as a composer rests on three or four orchestral works, the two sets of Shropshire Lad songs and very little else. We cannot know how he would have developed and whether he would have lived up to the great promise which Vaughan Williams and others saw in him. Nevertheless, this small but distinguished body of work has secured a place for him in the history of English music which will be forever linked with that Lost Generation.

Martin Holmes

- Log in to post comments

Comments

George Butterworth