The fourth congress diary sharing an aspect of the 2018 IAML Congress in Leipzig is by Geoff Thomason of the Royal Northern College of Music.

I must have been about eleven or twelve when I first became aware of Leipzig. While my contemporaries were enthusing about football I was discovering the music of J. S. Bach. Leipzig, of course, was mythical, as were most places to someone whose family holidays had never ventured beyond Anglesey. In this case, doubly mythical by virtue of being in the Neverland called abroad, which you’d seen on the news but never met anyone who’d actually been there. And it was in Germany. To a kid who grew up opposite a bombsite in a house with shrapnel marks on the banisters and whose grandparents had an air-raid shelter in their back garden, Germany meant one thing. Well, two if you included the 1966 World Cup; the other one, as Basil Fawlty was later to remind us, you didn’t mention.

Moreover, as I later learned, Leipzig was in East Germany, that ideologically remote communist enclave which conjured up images of androgynous athletes and the Berlin Wall. There was no way I would ever go to the city of my beloved Bach. Yet the more I travelled along the path of musical knowledge, the more my journeys took me to Leipzig. As I read about Wagner, Schumann, Mendelssohn or Grieg, I visualised them in a growing Leipzig of the imagination. This imaginary Leipzig formed the backdrop to a whole chapter of my Ph.D. on Adolph Brodsky and was still uppermost in my mind as I placed the last full stop in my paper for the IAML Congress exploring the musical links between the city and Manchester. Now I was going for real, and everything would be just as I had imagined it.

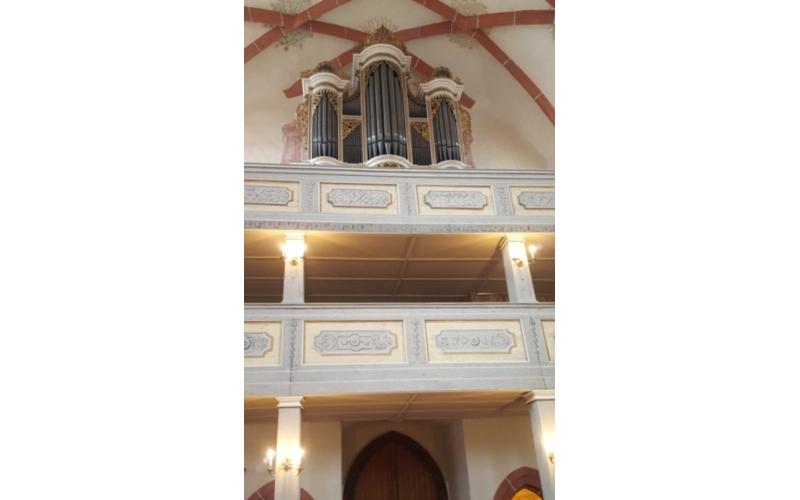

So that’s the Thomaskirche. It’s not where my mind had placed it. Which is harder to grasp, the slap of reality or that this is where the Matthew Passion first saw the light of day? And that’s the grave of the man whose mind conceived it. This is like Niagara Falls again; I can’t quite take in that I’m not looking at a picture any more. Why is the Hochschule so far away from the Gewandhaus? I’d always imagined Brodsky popping next door to give his chamber quartet concerts. This, though, is the building he latterly taught in; I can’t find any reference to him in the fascinating history which adorns the upper corridor, but there is a plaque to his ‘cellist Julius Klengel, and even if the RAF put paid to his office, he surely walked through that same entrance and up those steep steps that I’m now doing. The whole week becomes a series of experiences in which the real Leipzig mocks the naivety of my imagined one.

With the post-Congress tour to Dresden, things are rather different. I’d been here before, in 1994, when many of the scars of its recent history were still evident. Dresden was already no longer mythical and I was keen to see how much it had changed. Above all, I wanted to see the rebuilt Frauenkirche, which symbolised more than anything the city’s rebirth. “You can’t understand Coventry without Dresden”, my mother once said of my fascination with Dresden’s twin. Standing before the Frauenkirche, which I’d last seen as a pile of stones, was thus a kind of closure. Two damaged cities, two Phoenixes rising from their ashes, two beacons of peace and reconciliation. The ultimate experience in a week of powerful experiences.

Oh yes, the Congress. I was certainly there, and in other circumstances I might have devoted my prose to discussions of papers and presentations. But diary entries are personal things, and this was Leipzig, and no longer the Leipzig of my imagination. I worshipped in Bach’s Thomaskirche. I stood next to his mortal remains while hearing his music. I walked in the corridors where Adolph Brodsky had walked. I heard two wonderful Silbermann organs on the Wednesday excursion. And in Dresden the pile of stones on the Neumarkt had become the Frauenkirche again. Es ist genug.

All photos copyright Geoff Thomason.

- Facebook Like

- Share on Facebook

- Log in to post comments

Comments

Geoff Thomason's diary